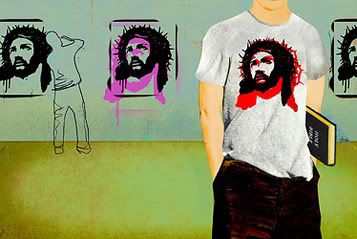

Sugarcoated, MTV-style youth ministry is so over. Bible-based worship is packing teens in pews now

By Sonja Steptoe / Bellflower

Posted Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2006

Sometimes a scavenger hunt is just a scavenger hunt. That’s all it is at many churches, where the frenzied chase to collect trinkets and complete silly tasks is a perennial activity aimed at getting teenagers into their doors. But at Calvary Baptist Church in Bellflower, Calif., a scavenger hunt is also a metaphor for the lifelong pursuit of meaning and happiness that begins in adolescence–and rich grist for a sermon targeted to teens. “A scavenger hunt is a search,” youth leader Doug Jones, 20, tells the 80 teens who have just returned from a race through this working-class city 30 miles east of Los Angeles. Quoting from Romans 10: 13 (“Anyone who calls on the Lord will be saved”) and Matthew 7: 7 (“Ask, and God will give to you. Search, and you will find”), he urges them to “ask God to come into your life and rescue you, and bring your personal scavenger hunt to an end.”

Youth ministers have been on a long and frustrating quest of their own over the past two decades or so. Believing that a message wrapped in pop-culture packaging was the way to attract teens to their flocks, pastors watered down the religious content and boosted the entertainment. But in recent years churches have begun offering their young people a style of religious instruction grounded in Bible study and teachings about the doctrines of their denomination. Their conversion has been sparked by the recognition that sugarcoated Christianity, popular in the 1980s and early ’90s, has caused growing numbers of kids to turn away not just from attending youth-fellowship activities but also from practicing their faith at all. In a national survey recently released by Barna Group, a polling firm that tracks religious trends, only 33% of kids 13 to 18 responded that they attend a youth-group event regularly–a 3% drop since 1998. And while nearly 75% pray each week, that number has declined 9%.

Even more worrisome to many youth ministers was the Barna survey finding that 61% of the adults polled who are now in their 20s said they had participated in church activities as teens but no longer do. Some experts point out that young people typically drift from organized religion in early adulthood, but others say the high attrition is a sign that churches need to change the way they try to engage the next generation of the faithful. “This dip should serve as an exhortation for everyone to be about the business of discipleship, missions and a higher calling than popcorn-and-peanuts youth culture,” says Ted Haggard, president of the National Association of Evangelicals. Scholars who have looked at young Christians say their spiritual drift is in part the result of a lack of knowledge about their faith. “The vast majority of teens who call themselves Christians haven’t been well educated in religious doctrine and therefore don’t really know what they believe,” says Christian Smith, a University of Notre Dame sociologist and the author of Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. “With all the competing demands on their time, religion becomes a low priority, and so they practice their faith in shallow ways.”

As the exodus has increased, churches are trying to reverse the flow by focusing less on amusement and more on Scripture. When Chris Reed failed to convert a single youngster during one 12-month period soon after taking over as youth minister at Calvary in 1995, he decided to restructure his young people’s program by adding both larger doses of doctrine and closer adult mentoring. Now, religious instruction, based on a model developed by youth pastors at Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church, centers on five Christian principles–evangelism, fellowship, discipleship, ministry and worship.

There’s still some fun, games and live-band music in the mix at Calvary, but every youth activity, from scavenger hunts to prayer meetings to scrubbing floors and donating food and clothes at Los Angeles homeless shelters, must relate to one of the principles. Additionally, Reed recruited parents and young adults like Jones to forge bonds with small groups of six to eight teens. The grownups lead weekly Bible studies, help plan missionary trips and monitor the high schoolers’ emotional and spiritual well-being with frequent phone calls and face-to-face encounters outside of church. Since Reed’s overhaul six years ago, the total youth rolls–including the reconstituted Sunday school and college programs–have grown from 70 to more than 200. In 2003, a record 64 teens accepted Christ as their savior at Calvary. “We’re healthy spiritually,” Reed says. He adds that even adults who once thought teen members had little to contribute and needed baby sitting welcome their involvement in all church activities.

Bible-based youth ministries at churches around the country are enjoying a similar success. At Shoreline Christian Center in Austin, Texas, youth pastor Ben Calmer vetoed the purchase of a pool table because it didn’t further his goal of increasing spiritual nourishment. Instead he started a class in which the young people wrestle with such difficult questions as, Why doesn’t God answer all prayers? No one seems to be suffering from the absence of the pool table. Youth membership has doubled, to 160, during the 18 months Calmer has been in charge. Similarly, teens at Covenant Life Church in Gaithersburg, Md., are embracing the big doses of Bible study youth pastors now recommend. Teen ranks have tripled, to nearly 600, since the mid-1990s.

The Calvary kids say they too are happy with the more traditional approach. Priscilla Balcaceres, 16, believes she would still be holding grudges and feuding with friends and family were it not for Bible lessons and sermons on forgiveness. “Before attending Calvary, I believed in God and prayed at night, but I was still very bitter and unhappy about many things in my life,” she says. “I’ve learned what it really means to be a Christian, and now I wake up smiling every morning.” Meanwhile, Amanda Sinks, 16, spouts verses from Timothy, Corinthians and James the way other teens recite rap lyrics. “There’s nothing boring to me about reading the Bible every day,” says Sinks, who became a Christian 17 months ago and counts a heightened ability to withstand peer pressure as one of the benefits. If things keep up this way, hanging out with God might even become cool.

Article printed in Time Magazine. Click here for original link.