(By James Davisson) – Many of you who know me, and—I suppose—all of you who don’t, may not know that I struggle with Pride. Pride is one of the Seven Deadly Sins recognized by the very early church, and it’s pretty much the deadliest. It is for me, anyway.

There’s a tendency to conceive of Pride as just an unhealthy excess of self-esteem, and while that’s definitely part of it, I think there’s a bit more to it than that. I don’t have any real problem with self-esteem; I generally know my place, and know that I am a fallen creature, though still loved and valued by God.

I just never, ever want to be wrong about anything.

Ask pretty much anybody who’s been on a missions trip with me, or had to live with me in close quarters for a long time. Ask David Witthoff, who had to put up with my nonsense for a whole summer this year, in a hot, hot country with nothing to do but talk while you wait for it to be not-hot. Eventually it comes out: I’m a cool cucumber until someone flatly tells me I’m wrong about something I’m dead sure I’m right about. And I think just about everybody’s like this. And it’s Pride. And it’s Wrong.

Two questions come to mind: first, why are people like this? Second: why is it wrong?

Here’s why people think they’re right all the time. In my experience, you get strong opinions in two ways: by thinking really hard about the issues at hand, or by being told what to think by someone you respect and believe in. I find that most of my opinions come from option two, and most of the time I think they are from option one. At all events, these feel like great reasons to believe something strongly; and they are great reasons. Independent thought is great, and so is trusting those who are worthy of respect. But, while you might think that opinions from option two are a lot worse than those from option one, when you boil it down, they’re both opinions.

The problem, in short, is this: we are—as I said before, of myself—fallen creatures. With fallen reason. This means that we are stuck knowing only in part what God knows in full. However hard we think, we are still never going to get it all right. Check out this scripture:

(Forgive me for talking so long before getting to scripture. I like the sound of my own authorial voice, I guess. Pride, see?)

Matthew 21:28-32 (NRSV)

28 ‘What do you think? A man had two sons; he went to the first and said, “Son, go and work in the vineyard today.” 29He answered, “I will not”; but later he changed his mind and went. 30The father went to the second and said the same; and he answered, “I will go, sir”; but he did not go. 31Which of the two did the will of his father?’ They said, ‘The first.’ Jesus said to them, ‘Truly I tell you, the tax-collectors and the prostitutes are going into the

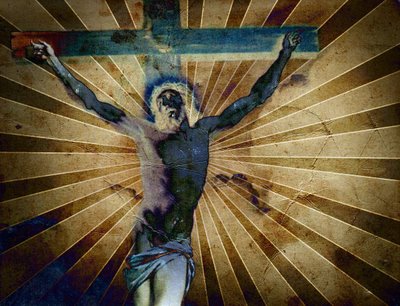

This gospel passage reminds us of our conversion from the way of sin: we Christians are all the brother who, when asked to go work in the vineyard, replied ‘I will not,’ but later changed his mind and went to work in the field; we are all ‘the tax-collectors and the prostitutes . . . going into the kingdom of God;’ we are all sinners made whole by the death and resurrection of Christ.

A steadfast refusal to admit even the possibility that someone who disagrees with you is right is a sin. In placing your opinion, which you got from fallen reason, totally above someone else’s, you put yourself above them. You forget that we are all sinners, and that none of us can know fully. You commit the sin of Pride.

Thomas à Kempis said: ‘A true and humble estimate of oneself is the highest and most valuable of all lessons. To take no account oneself, but always to think well and highly of others is the highest wisdom and perfection.’ When you get into an argument—about, pretty much anything, mind including interpretations of any fine point of scripture (I’m talking to you, people on both sides of the predestination debate. And the abortion debate. And the gay rights debate. Seriously.)—take no account of yourself. Consider the other person better than yourself. Argue peacefully, and respectfully. In my experience, there is no greater preserver of friendships than the skill of disagreeing civilly—agreeing to disagree.

“who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited, but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.” (Philippians 2:6-7